A fundamental biological process governing chromosome pairing during egg and sperm development is now understood with unprecedented clarity. New research from the University of California, Davis, published in Nature, reveals how errors in this process directly contribute to infertility, miscarriage, and genetic conditions like Down syndrome.

The Critical Role of Chromosome Crossovers

Humans inherit 23 pairs of chromosomes – one set from each parent. During the formation of sperm and eggs, these pairs must exchange genetic material in a process called crossover. This ensures genetic diversity in offspring while also physically linking the chromosome pairs. Without proper crossovers, chromosomes can separate incorrectly during cell division, leading to egg or sperm cells with the wrong number of chromosomes. This is the underlying cause of many reproductive failures.

How the Process Works: Double Holliday Junctions

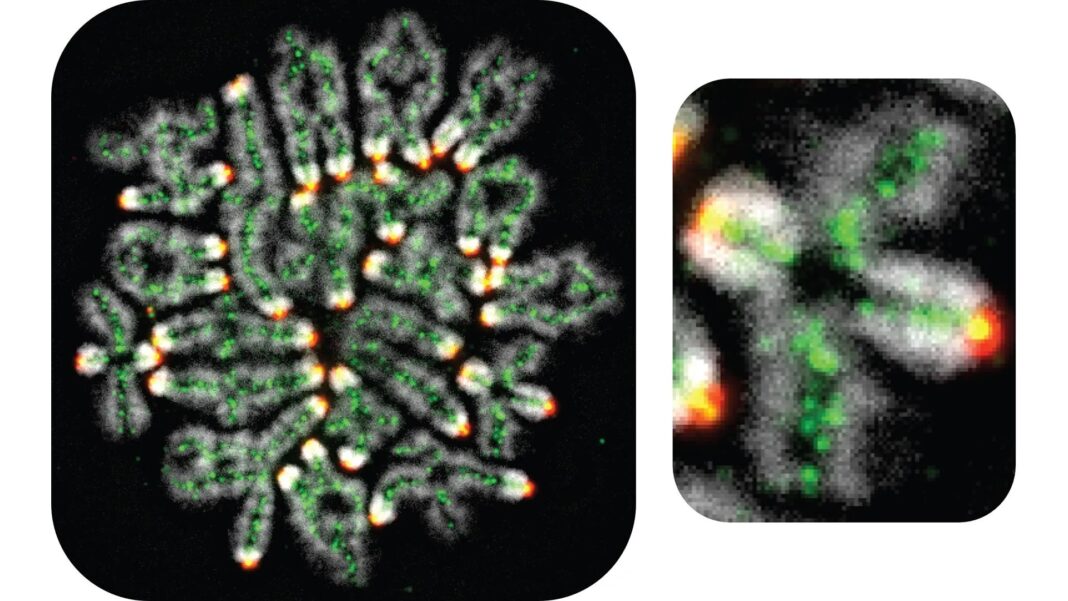

The crossover process involves a structure called a double Holliday junction where DNA strands from paired chromosomes intertwine. Enzymes then cut and rejoin these strands, forming a stable connection. Researchers led by Professor Neil Hunter used genetic engineering in yeast (a model organism with remarkably similar processes to humans) to observe these molecular events in real-time.

The Problem with Broken Connections

If these junctions fail to form properly, chromosomes can become disconnected, like people losing grip in a crowd. This leads to egg or sperm cells with either too many or too few chromosomes. Down syndrome, where a person has an extra copy of chromosome 21, is a direct result of this error. Miscarriage and infertility are also common outcomes.

Why Females Are More Vulnerable

Egg cells face a unique challenge: they form crossovers early in development but remain dormant for decades in a female’s ovaries. Maintaining these connections over such long periods is critical, as damaged crossovers can lead to errors when the egg is finally activated. In contrast, sperm cells divide and distribute chromosomes much faster, reducing the risk of long-term connection failures.

Key Proteins Identified

Hunter’s team identified proteins such as cohesin that protect the double Holliday junctions from premature breakdown. Another complex, the STR complex (or Bloom complex in humans), is kept in check by these protective proteins, ensuring that crossovers form correctly. By systematically disabling proteins in yeast cells, the researchers mapped out the network of proteins required for successful crossover formation.

From Yeast to Humans: Evolutionary Conservation

The beauty of this research lies in its broad relevance. The fundamental mechanisms of chromosome crossover have changed little over evolution. The same proteins that function in yeast also work in humans, meaning insights gained from model organisms directly apply to human reproductive health. This understanding could lead to better diagnostics and treatments for infertility and genetic disorders.

The study underscores how fragile the process of reproduction is at the molecular level. Protecting these connections is not just about preventing errors—it’s about safeguarding the viability of future generations.